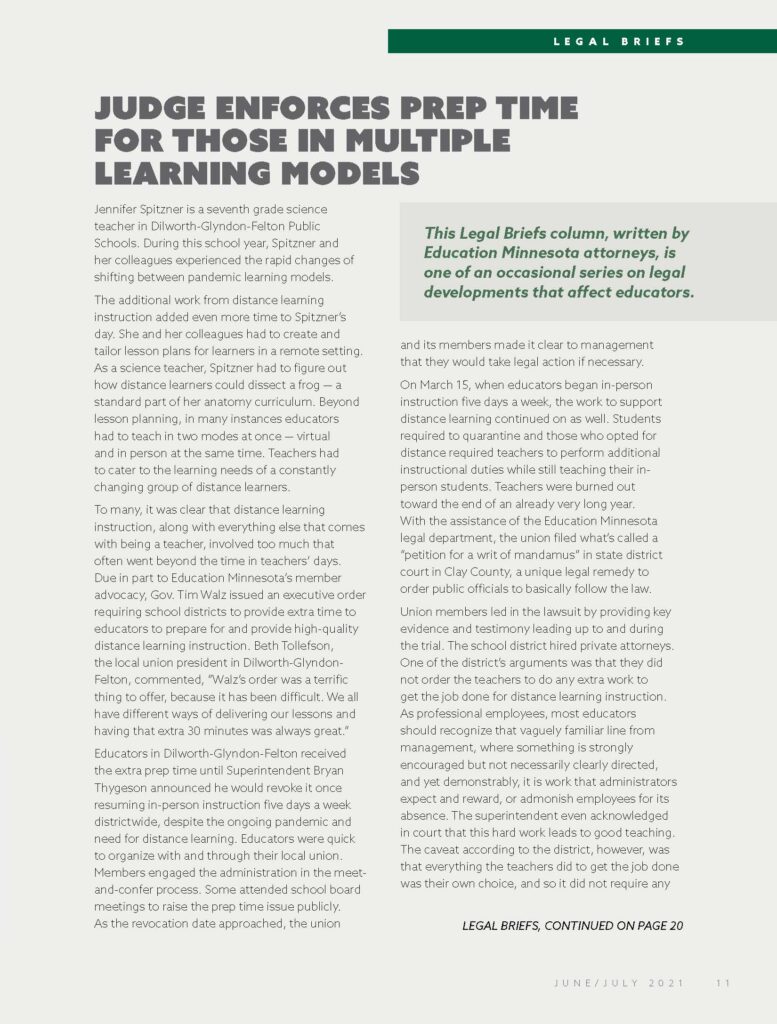

Jennifer Spitzner is a seventh grade science teacher in Dilworth-Glyndon-Felton Public Schools. During this school year, Spitzner and her colleagues experienced the rapid changes of shifting between pandemic learning models.

The additional work from distance learning instruction added even more time to Spitzner’s day. She and her colleagues had to create and tailor lesson plans for learners in a remote setting. As a science teacher, Spitzner had to figure out how distance learners could dissect a frog — a standard part of her anatomy curriculum. Beyond lesson planning, in many instances educators had to teach in two modes at once — virtual and in person at the same time. Teachers had to cater to the learning needs of a constantly changing group of distance learners.

This Legal Briefs column, written by Education Minnesota attorneys, is one of an occasional series on legal developments that affect educators

To many, it was clear that distance learning instruction, along with everything else that comes with being a teacher, involved too much that often went beyond the time in teachers’ days. Due in part to Education Minnesota’s member advocacy, Gov. Tim Walz issued an executive order requiring school districts to provide extra time to educators to prepare for and provide high-quality distance learning instruction. Beth Tollefson, the local union president in Dilworth-Glyndon-Felton, commented, “Walz’s order was a terrific thing to offer, because it has been difficult. We all have different ways of delivering our lessons and having that extra 30 minutes was always great.”

Educators in Dilworth-Glyndon-Felton received the extra prep time until Superintendent Bryan Thygeson announced he would revoke it once resuming in-person instruction five days a week districtwide, despite the ongoing pandemic and need for distance learning. Educators were quick to organize with and through their local union. Members engaged the administration in the meet-and-confer process. Some attended school board meetings to raise the prep time issue publicly. As the revocation date approached, the union and its members made it clear to management that they would take legal action if necessary.

On March 15, when educators began in-person instruction five days a week, the work to support distance learning continued on as well. Students required to quarantine and those who opted for distance required teachers to perform additional instructional duties while still teaching their in-person students. Teachers were burned out toward the end of an already very long year. With the assistance of the Education Minnesota legal department, the union filed what’s called a “petition for a writ of mandamus” in state district court in Clay County, a unique legal remedy to order public officials to basically follow the law.

Union members led in the lawsuit by providing key evidence and testimony leading up to and during the trial. The school district hired private attorneys. One of the district’s arguments was that they did not order the teachers to do any extra work to get the job done for distance learning instruction. As professional employees, most educators should recognize that vaguely familiar line from management, where something is strongly encouraged but not necessarily clearly directed, and yet demonstrably, it is work that administrators expect and reward, or admonish employees for its absence. The superintendent even acknowledged in court that this hard work leads to good teaching. The caveat according to the district, however, was that everything the teachers did to get the job done was their own choice, and so it did not require any additional compensation, time or even recognition.

The district also argued that the 2020-21 school year was just like any other year, in that the work teachers had to do to support distance learning was just like kids going on vacation or being out sick for a couple days for the flu. Judge Jade Rosenfeldt of the Clay County District Court reasoned that the district’s “argument that quarantined students are no different from students in years past being gone for an illness and/or vacation is simply thoughtless.”

Ultimately, the law from the executive order was clear — if teachers had distance learning students, they were due the extra prep time. The judge recognized that clarity. In her final decision, she found that the Dilworth-Glyndon-Felton teachers had been working without an additional 30 minutes of prep time to which they were entitled under the law, and that teachers were indeed teaching students in both distance learning and hybrid learning models.

The judge ordered the school district to immediately follow the law. With the great hope of the conclusion of the pandemic, educators around the state look to the future for what their profession will look like and how it is perceived and addressed by stakeholders. Educators, when acting together, are powerful and can have a say in what their work looks like. And the educators in Dilworth-Glyndon-Felton showed that strength to their community and the rest of the state.

– Jonathan Reiner

Education Minnesota staff attorney